Inclusion first: how social enterprises are rethinking recruitment

Bosses and hiring managers need to be proactive if they want to hire a diverse team. From writing your job description to interviews and beyond, we explore some of the potential pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Plenty of organisations made ambitious pledges to be more inclusive at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests last summer. Since then, many social enterprises have enlisted diversity consultants, developed inclusion plans and trained their employees about biases and privilege.

One crucial piece of the puzzle when it comes to inclusion is the recruitment process. Whether it’s writing the job description, interviewing or hiring a candidate, each step presents pitfalls that can trip up even the best-intentioned hiring manager.

Social enterprise leaders and experts share their tips and tools, what’s worked so far and what still needs attention.

1. The job description

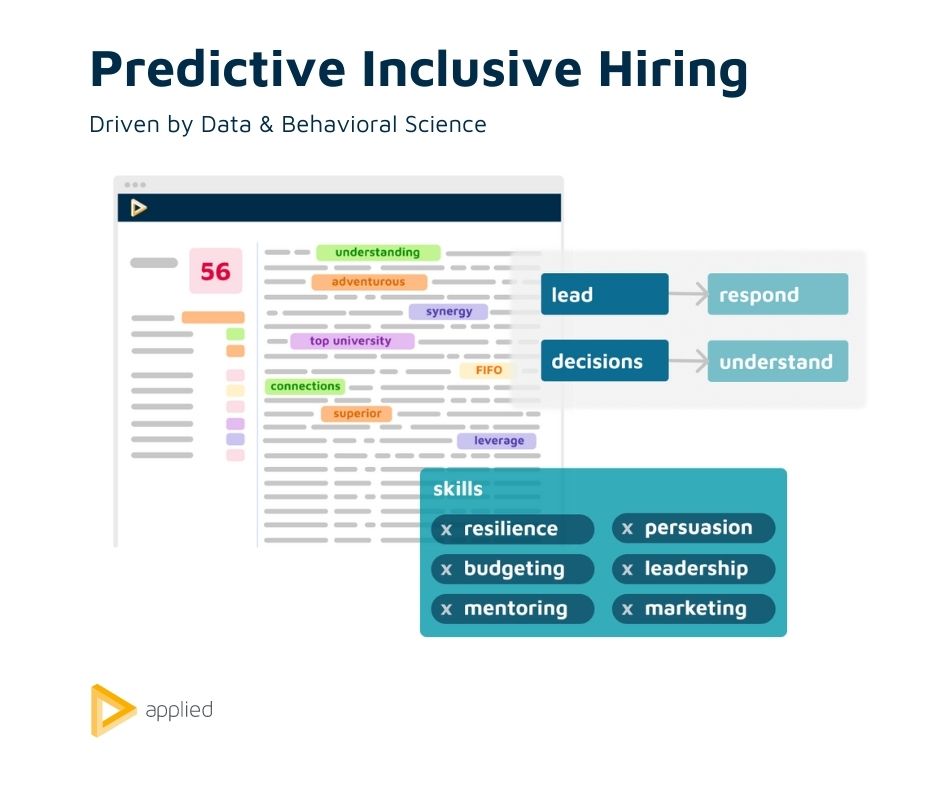

Recruitment platform Applied, which uses “blind” recruitment software that cuts out the use of CVs, helps employers to avoid biases at each stage of the hiring process – starting with the wording of a job advert.

Community lead WuQing Hipsh says that inclusive recruitment “starts with having a good funnel of diverse applicants,” which is rooted in what the job application asks for and how it is written.

Community lead WuQing Hipsh says that inclusive recruitment “starts with having a good funnel of diverse applicants,” which is rooted in what the job application asks for and how it is written.

“Don’t ask for experience or degrees,” she says, “focus more on explaining a day in the life of the job”. The Diversity Forum’s toolkit for the social investment sector echoes a similar sentiment. It suggests that employers should “limit the list of requirements to a few ‘must-haves’” rather than a certain number of years’ experience in a sector: lived experience is just as valuable as career experience, the authors write, as not everyone will have been to university or followed a ‘conventional’ career path.

Don’t ask for experience or degrees, focus more on explaining a day in the life of the job

Language also plays a part in people feeling like the right person for the role. Scottish social enterprise agency Firstport has made a number of changes in how it recruits, including how it words job descriptions. It uses a free online Gender Decoder tool which quickly scans text and highlights certain words that may be considered as gendered – for instance the word ‘assertive’ is often linked to men, whereas ‘caring’ is seen as a more feminine trait. “Our roles come across as more female, perhaps because of the nature of them,” Firstport head of communications Maria Ashley explains; the tool aims to try to “balance out” the gender of applicants. Firstport staff are still predominantly female, though, so there is still work to be done.

2. Advertising the role

“People have to ask themselves honestly, ‘what is our reach?’” says Sacha Rose-Smith, director of programmes and learning at the School for Social Entrepreneurs (SSE). She suggests that people have got “a little bit lazy” as a result of technology, assuming that posting a vacancy on their website or on social media will reach enough potential candidates. To break out of the echo chamber, organisations can partner with others that have a different reach from their own – for example, SSE works with Ubele, the social enterprise supporting projects led by the African diaspora in the UK, to help it to attract more Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates.

Advertising with specialist jobs boards or networks can attract a wider pool of applicants, and can show that your organisation is open to difference. Jane Hatton founded Evenbreak in 2011, a specialist jobs board for – and run by – disabled people. In research by University College London, on behalf of Evenbreak, more than 82% of disabled candidates said their most pressing problem was “finding truly disability-friendly employers”. The social enterprise charges employers to access its candidate pool, and Hatton believes that this paid-for model tests their commitment to hire disabled candidates. “Disability is high on their agenda and they're genuine about inclusion,” she says.

Advertising with specialist jobs boards or networks can attract a wider pool of applicants, and can show that your organisation is open to difference. Jane Hatton founded Evenbreak in 2011, a specialist jobs board for – and run by – disabled people. In research by University College London, on behalf of Evenbreak, more than 82% of disabled candidates said their most pressing problem was “finding truly disability-friendly employers”. The social enterprise charges employers to access its candidate pool, and Hatton believes that this paid-for model tests their commitment to hire disabled candidates. “Disability is high on their agenda and they're genuine about inclusion,” she says.

Other jobs boards and recruitment agencies support all kinds of diverse talent. For instance in the UK, Working Chance matches women with past convictions to suitable job opportunities, and Rare Recruitment is designed to make elite professions more racially diverse.

3. Evaluating applicants

There’s not much that you can’t find out about someone through a simple online search. For employers, this can be a first insight into potential candidates, but it can also prompt superficial assumptions. SSE suggests trying a simple Google Chrome extension called Unbias Me, which hides a candidate's profile picture and name when you're looking at their LinkedIn page or Twitter feed.

Sometimes, our assumptions are even less conscious. “Our brain has two ways of thinking – fast and slow,” says Hipsh. “We make shortcuts to save time and energy, so we’ll never be able to debias our quick reactions. You have to design structures to make you slow down.” Applied will group every candidate's answers to the same question together, rather than sharing one candidate’s entire application form. This is to challenge confirmation bias – the tendency of humans to look for information that confirms existing beliefs. Here, for example, it could ensure that application reviewers are not unconsciously expecting someone with a good education to give intelligent answers.

We’ll never be able to debias our quick reactions. You have to design structures to make you slow down

But there’s no perfect solution. Social investment wholesaler Big Society Capital has recruited around 30 staff members through Applied in the past three years. HR manager Ruth Davidson is an advocate of the approach, but believes that biases can still infiltrate the process, even without names and CVs on applications. She sees the platform as just “one piece of the puzzle”, and wonders whether we still end up making judgements about grammar and structure of written answers, rather than purely focusing on what a candidate is trying to communicate.

But there’s no perfect solution. Social investment wholesaler Big Society Capital has recruited around 30 staff members through Applied in the past three years. HR manager Ruth Davidson is an advocate of the approach, but believes that biases can still infiltrate the process, even without names and CVs on applications. She sees the platform as just “one piece of the puzzle”, and wonders whether we still end up making judgements about grammar and structure of written answers, rather than purely focusing on what a candidate is trying to communicate.

And people express themselves in different ways. SSE’s Rose-Smith suggests that employers should consider unconventional application approaches, including video or audio responses. “We rule out a lot of people by not providing alternative options,” she says.

Another option: get rid of applications entirely. Open hiring involves no interviews or background checks, just a simple set of basic requirements. Whenever an opening comes up, almost everyone who meets those will be able to get a job on a first-come, first-served basis. Organisations including the Body Shop, Timpson (pictured), and Greyston Bakery (who pioneered the approach) are among those using open hiring in an effort to be more inclusive.

4. The interview

Interviews are by their very nature subjective. But there are ways to give candidates the most fair opportunity to prove their suitability. Hatton at Evenbreak explains that employers should consider the needs of their applicants, and be open to making adjustments. For example, someone with autism may feel “a bit less anxious” if they’re given an idea of the questions in advance, or if they know how many people will be on the panel.

The results of Firstport’s recruitment round for an engagement and outreach officer in December suggests there’s something in this. It received more than double the number of applicants than normal, and Ashley believes this was partly thanks to their efforts to be very transparent about the process.

Simply ensuring you ask every candidate the same question can also mitigate biases from interviewers. Applied’s research shows that in job interviews, women are often asked ‘preventional questions’, like how they would deal with financial losses, whereas men are often asked ‘promotional questions’, like how they would monetise a product. The phrasing of these questions can link women to the idea of risk while men are connected to gain. “If you're asking everyone the same question, then there is a degree of fairness and objectivity, giving everyone the same opportunity,” says Rose-Smith.

It’s also about asking the right questions. “You're not recruiting somebody as a skill, or as an experience, you're recruiting them as a person,” she says. So, getting a feel for their attitude and drive is key. “You can teach somebody to do a job, you can't teach somebody to care about the mission or purpose of an organisation.” And Rose-Smith suggests we need to shake up the whole process – not least addressing “the power imbalance of interviews” – to come up with something more creative and more inclusive. “We need to shift what we’ve always done, to what is possible”.

You can teach somebody to do a job, you can't teach them to care about the purpose of an organisation

5. Hiring candidates

Inclusivity doesn’t stop once a candidate has been hired. This is just the beginning of a new process. But, when considering disabled access, for example, Hatton emphasises that “employers aren't expected to be experts”, because “every disabled person is an expert on their own access”. By employing disabled people, organisations will automatically become better at catering for those with different needs, and will be informed by each new recruit.

And more broadly, Rose-Smith believes that organisations need to consider “how inclusivity is embedded in everything” – from the culture to how meetings are run. She shares a personal example: her dyslexia means that she needs to visualise directions to find her way to places. She recently went to a meeting where the organisation had a video of their building and street layout on their website. It was a small but important example of inclusivity for her.

“We need to constantly be alive to inclusivity, it’s a part of company culture that has to live and breathe – and it's never a finished idea,” she says.

Images: Applied's job description tool can analyse roles and suggest changes to make it more inclusive; social entrepreneurs learning together at SSE Midlands, on the School for Social Entrepreneurs’ biggest UK programme (credit: SSE); employees at Timpson, a business where around 10% of staff are ex-offenders (credit: Timpson)

Thanks for reading Pioneers Post. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.